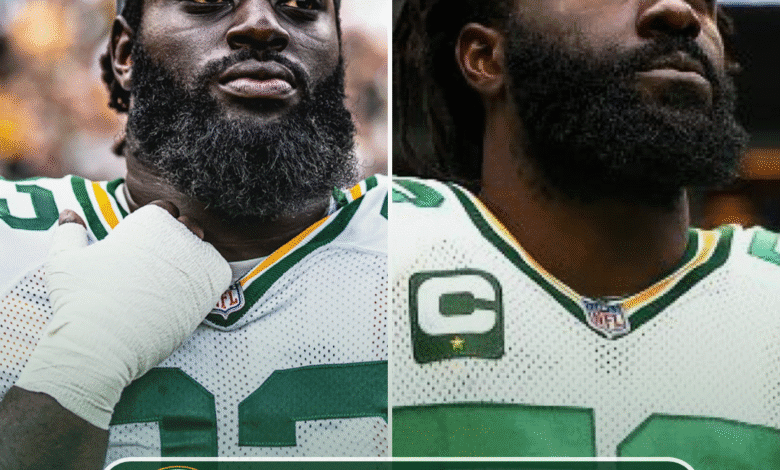

Nazir Stackhouse Turned the Odds Into Opportunity, Proving Football Is More Than a Game for the Undrafted Packers Star.QQ

ajeeyah Howard doesn’t get nervous…typically. There’s an inner confidence within this vibrant, high-spirited woman that one way or another things will work out as intended.

This August morning down in Georgia felt different, though.

Nearly 1,000 miles away, Howard’s son, Nazir Stackhouse, was waiting to hear whether he’d made the Packers’ roster as an undrafted free agent.

And mom couldn’t be there.

Howard, the woman responsible for signing this 6-foot-4, 327-pound defensive tackle up for football, was reduced to periodically checking her phone for updates while managing a busy workday at Family Dollar.

It was an unfamiliar, helpless feeling for Howard, who moved heaven and earth for the past decade to attend nearly every football game her son played, from little league to the SEC.

“I was unloading the truck with my Green Bay shirt on, just sad I couldn’t be there,” Howard said. “It was the biggest moment we’ve been waiting for and here I am unloading this truck, pulling my back out.”

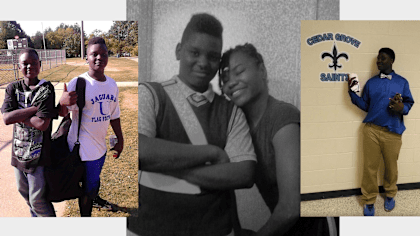

Howard introduced Stackhouse to the game to build his self-esteem while also keeping her son on a successful path. A love for the sport of football soon sprouted for mother and son.

A transformative five years at the University of Georgia saw Stackhouse grow as both a man and a football player. Howard was there for the high of winning back-to-back national titles with the Bulldogs and the low of going undrafted this past April.

The big man with a big personality earned an opportunity in Green Bay, though. While Stackhouse promised to let mom know if he’d made the team, Howard kept checking.

Noon. One o’clock. Two. Even when news reports started trickling out that her son made the team, Howard waited for that call. Once practice was over, Stackhouse quietly went to a focus room inside of Lambeau Field to deliver the news.

He’d made it.

“I just wanted to embrace the moment because there’s a lot of hard work put into getting that answer,” Stackhouse said. “I was just very, very thankful for it.”

Football is just a small part of Stackhouse’s story. It’s a testament to willpower, grace and sacrifice. It’s a young kid who overcame personal adversity and a silent battle with narcolepsy to establish himself as a prospect in a football hotbed.

It’s a hard-working mom pulling overnights, punching out at 2 a.m. and driving hundreds of miles through the dead of night on not a wink of sleep to watch her son play that afternoon.

When Howard found out her son made the team, you better believe there was hollering in the store.

“You’d thought I was a Green Bay Packer player,” Howard said. “You’d thought I was the one who got put on the roster.”

Early signs

Before Stackhouse even played football, there were signs it might be his sport. How else do you explain a 5-year-old running around with a broken wrist like nothing’s wrong?

But that was the reality with which Howard was presented after her son came home one day reporting pain in his wrist.

Stackhouse was playing on a track ride at the playground before baseball practice when one of his brothers bumped into him, causing Stackhouse to tumble to the ground with one hand behind his back and the other breaking his fall.

He laughed it off, at first. Stackhouse still practiced while favoring his wrist during fielding drills. Once home, Stackhouse told his mom what happened and that he may have sprained it.

Tests proved otherwise.

“Ain’t no way in God’s green earth you could be moving around and doing what you’re doing like it’s not broken at all. That’s when I knew he was a football player.”-Rajeeyah Howard, Nazir Stackhouse’s mom

After putting ice on it, it took no more than 10 minutes and “that thing swelled up like a doggone balloon.” Howard drove her son to the hospital. This was no sprain or even a hairline fracture. X-rays showed Stackhouse broke his wrist, straight across.

“Snapped it in half,” said Stackhouse with a laugh. “It was cooked.”

Stackhouse was given a harness and instructed to wait a couple weeks for the swelling to go down before surgery. During that time, the elastic bandage on the youngster’s wrist was the only indication of anything being out of the ordinary.

“The way this man hurt himself, ain’t no way in God’s green earth you could be moving around and doing what you’re doing like it’s not broken at all,” Howard said. “That’s when I knew he was a football player.”

Seeing her son’s size and natural ability, Howard went down to Wal-Mart with her brother and bought every piece of football equipment they had in stock to put that suspicion to the test, going so far as to even set up a little football field in the yard.

But Stackhouse had to want to play and that was the decision he faced after moving from New Jersey to Georgia when he was 7.

One day, while Stackhouse was on the playground at Wade Walker Park, Howard noticed kids playing football across the street. She asked her son if he wanted to join in. Stackhouse said sure and Howard walked straight up to the coach to inquire.

“As soon as he saw me, the coach was like, ‘Oh yeah, he can practice right now,'” Stackhouse said. “I was like, ‘Right now?’ I was enjoying my time at the park. I’m not ready to practice, but I ended up practicing the next day.”

Turning into a football player

Football didn’t immediately take for Stackhouse, who learned on the first day how grueling the game could be.

When asked to run a lap around the park before practice, Stackhouse didn’t think he’d make it. Once tackling started, he appealed to his mom about why the kids were hitting so hard.

“The first time Nazir got on that football field, honey, you talk about crocodile tears. I’m talking about tears the size of Mount Rushmore,” Howard said. “That man cried every day just about. But after the first season, after the first go-around with him trying football, Nazir was a beast.”

Within a year, Stackhouse was the one lowering the boom and the ball carriers were begging him to let up. He developed a strong support system that included youth coaches Valister Wilson and Corey Newsom, whose son Nico was a teammate and friend of Stackhouse.

“Naz was like a big wrecking ball. … His name would always get brought up because he was one of the biggest kids on the field.”-Packers CB Micah Robinson, Stackhouse’s Future Stars Game teammate

Newsom coached Stackhouse on the defensive line in park league and was the first to see something in the child – not only the youngster’s size and ability but also his on-field demeanor.

Howard remembers going to pick up Stackhouse from practice one day when Newsom pulled her to the side and directed her attention to watching her son on the field.

“I want you to look at your son,” Newsom told her. “When Nazir gets on the field, he turns into a different person. In his stance, for some odd reason, it just seems like he blocks everything out.”

He was right. To this day, Stackhouse is never more focused than when standing on a football field. The laughing and giggles subside between those white lines.

Playing for the Central DeKaub Jaguars, a determined Stackhouse started to get noticed in the Atlanta area. He received invites to local camps and a spot on Team Georgia in the Future Stars Game.

He was joined by current Los Angeles Chargers running back Kimani Vidal and future Packers teammate Micah Robinson, who played alongside future Minnesota Timberwolves star Anthony Edwards on the Atlanta Vikings.

“We all had the same goal in mind, wanting to go to the NFL, wanting to go to the league,” said Robinson. “Naz was like a big wrecking ball. Before games, we were doing scouting reports for little league and his name would always get brought up because he was one of the biggest kids on the field.”

By high school, Stackhouse met two more influential figures in his life in Stephenson (Ga.) High defensive line coach Gary Kimpson and recruiting coordinator Corey Johnson, who would drive Stackhouse to school from his mom’s place in Decatur.